When visiting lighthouses built in the 19th century, you may notice a strange hive like glass cage around the lamp. These are the Fresnel lenses, originally designed by Augustin Fresnel*. At the time, lighthouses were starting to use lenses to extend the distance of the light beam. However, they faced a problem with traditional lenses, which were heavy and lost a lot of light. Fresnel realized that a lot of bulk glass could be removed and designed the strange lens with concentric stepped rings and a flat back. This new design collimates the light and reduces the loss. Today, they have many applications from bike lights to magnifying text. In this article we will learn how they work and how they can be used.

An example of a first order Fresnel lens used by lighthouses, which is on display at the San Francisco Maritime Museum. Courtesy of National Park Service

A Review of Traditional Lenses

A traditional converging lens consists of at least one convex face. This face usually has spherical curvature, though other shapes are also used. For instance a parabolic lens will have fewer aberrations, but will be much more expensive. Other lens shapes include conical and cylindrical. Further, the way the lens is arranged will impact the way a lens focuses. For instance, having two convex surfaces will create a diverging lens in which the focal point lies behind the lens. On the other hand, prescription glasses usually have a meniscus shaped lens, where one side is convex and the other is concave. In all cases, the curvature of each surface can differ. These parameters all affect the focal length and magnification of the lens.

The key element for lenses is the refractive index of the material they are built out of. This is a property of the material that makes up a lens. For example, air has a refractive index of 1 (it’s actually slightly greater than 1 but is often rounded down for simplicity) and glass has a refractive index of 1.52. When a beam of light travelling in air is incident on a glass surface, it will refract.

Using Snell’s Law, you can calculate how much a light ray will bend based on the refractive index of the materials, and the incident angle. If the surface is curved, like in a lens, then the amount of refraction of the incident light will depend on the distance of the incidence point from the optical axis. Parallel light rays incident on a convex surface will bend towards the optical axis, and converge at a focal point.

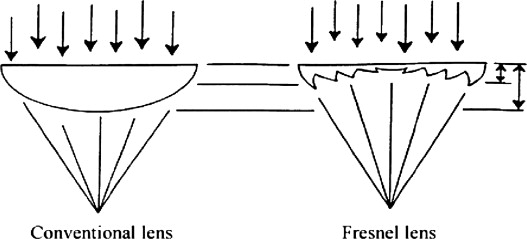

An illustration of a traditional lens compared to a Fresnel Lens. Courtesy of the Journal of Material Science

What is Different About Fresnel Lenses?

When looking at a Fresnel lens from a lighthouse, you’ll notice two distinct parts. The first is the set of rectangular pieces that sit around the center of the lens. This is what a typical Fresnel lens looks like, and is the main part of a Fresnel lens. Unlike a traditional lens, the surface of a Fresnel lens is broken up into rings that are arranged like a sawtooth when viewed from the side. This can be seen in the image above.

The top and bottom of the hive like structure are engineered to reflect the light that would otherwise be lost. These panes have a stepped edges on both sides of the material, instead of just the outer surface and employ total internal reflection, which occurs when light hits a surface at or above the critical angle. The angle of the reflector’s grooves is specifically designed with this critical angle in mind. The light rays from the source have a small incident angle so they are captured by the prism

Courtesy of Inside Science

The central light source radiates light in every direction and is very close to the lens, especially compared to the kilometer length scale the transmitted beam travels. As a result, the lens needs to have a short focal length so the light will focus into a collimated beam. Choosing the right focal length is important to ensure the light reaches its maximum range.

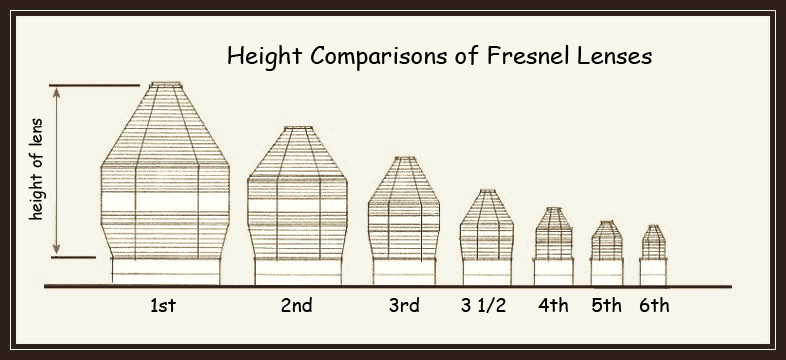

As a result, Fresnel created a 6 order system, detailing the size of each component, the focal lengths, where to use each order, and even the number of wicks for the central light source. This list was expanded later to include a few larger and smaller lenses. The first order, and originally the largest, Fresnel lens has a focal length of 92 cm and an approximate visibility of 35 km. On the other end, the sixth order Fresnel lens has a focal length of 15 cm and a visibility of 8 km.

Size differences in Fresnel Orders. Courtesy of CHSD.

Are lighthouses the only use for Fresnel Lenses?

Though they were originally deigned for use in lighthouses, Fresnel lenses are useful anywhere a concentrated beam of light is needed. Today, many bike lights use a Fresnel lens to increase visibility for a biker and for vehicles around them. Plastic Fresnel lenses provide extra magnification when reading, though there is often distortion, especially near the edges. Examples of Fresnel lenses, available for purchase can be found here.

With the need for alternative energy sources, solar energy is gaining a lot of attention. One of the main drawbacks for solar energy is the inefficiency of many solar cells. They are unable to make full use of the solar energy entering our atmosphere. Fresnel lenses offer a solution, by concentrating light at the solar cell surface.

Since many applications focus on the visible light wavelength range, they can be made of plastics, which reduce the cost and weight even more. This was first done with a mold, though today there are many techniques for creating structures on material surfaces. This is possible because many plastics are transparent to visible light. However, UV or IR wavelengths requires lenses to be made of a different material.

Drawbacks of Fresnel Lenses

While Fresnel lenses work very well for collimating a bright central light source, they can also be used to focus incoming collimated light. However, the placement of the lens needs to be precise to minimize the amount of aberrations that occur. The two most notable aberrations are spherical and chromatic. In both cases, the aberrations can be fixed with a multi-lens system, where light passes through more than one lens, whose curvature, focal lengths, and material properties can be specifically chosen.

Spherical aberrations occur when the light rays at the edge of the lens are focused at a different location than the rays near the center. This is caused by the shape of the lens, which most often has a spherical curvature. Changing the lens shape to have a parabolic curvature can correct the aberration, but will cost much more. A more cost effective route is to increase the radius of curvature of the lens, so the rays at the edge and the center are focused to the same point. However this increases the focal length of the lens.

Chromatic aberrations, on the other hand, result from different wavelengths of light being refracted at different angles. The extent of this is determined by the lens properties. This is especially important to consider when using a polychromatic light source, like an incandescent bulb. In this case, the light source consists of the entire visible light spectrum, and the red wavelengths will refract at different angles than the blue wavelengths. Chromatic aberrations are harder to correct since they stem from the natural property of the lens material. However, most applications for Fresnel lenses do not require this step so chromatic aberrations are expected and tolerated.

Aside from spherical and chromatic aberrations, Fresnel lenses also suffer from distorted images. This means the image seen after light passes through the Fresnel lens will not be a perfect replica of the original object. When using a Fresnel lens to magnify text, the letters and words may be harder to distinguish especially at higher magnifications. This trait limits the effectiveness of Fresnel lenses as a tool for magnification. Of course, this has no impact on a bright white light like a lighthouse.

*Note: Fresnel was not the first to try to split traditional lenses to reduce their weight, but he came up with a practical and affordable design for use in Lighthouses.