The Dilemma of Overfishing

The phrase, “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime” explains how teaching can be much more valuable for someone, as opposed to just giving them a “fish.” In recent years, humanity has taken this phrase almost too literally. Fishing has most likely been used for food for tens of thousands of years. The oldest rod and net were found in ancient Egypt, in 3500 BCE. However, with technologies allowing for fish to be caught at large rates, overfishing has become a pressing issue. Overfishing is when fish are caught too quickly, and cannot be adequately replaced within the ocean. It mostly occurs with bycatch, which are the ocean organisms caught in nets, which were not the original targets. Moreover, it is leading to the decline of sea turtles and other marine life. Overfishing is not only a problem for the ocean environment, but also fisherman and groups of people who depend on fishing as a way of life.

Orange Roughy being fish in large nets and emptied into a trawl. Courtesy of WorldWildLife

In 2019 in the United States, fishing was a $8.7 billion industry. With 64,000 companies fishing, on top of commercial fishing, there are 50.1 million people who recreational fish every year. In 2017, in the United States, 9.5 billion pounds of seafood was harvested for commercial use from the ocean. During the same year, recreational fishing is estimated to have caught 397 million fish. According to the 2018 edition of the Food and Agriculture Organization’s “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture”, 33% of fish populations experience overfishing.

Faculty at the University of Bergen, in Norway, recognize the many dangers of overfishing, and researched different ways to use photonics to combat this issue.

Laser Use in Iceland

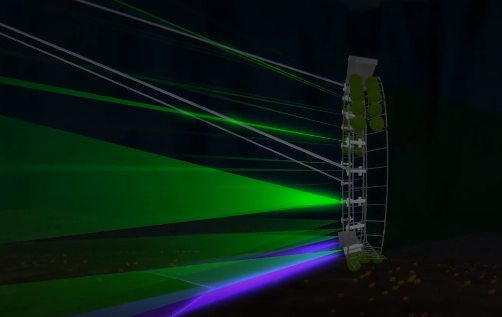

A startup in Iceland called Optitog is taking advantage of prawns being able to see laser light. Optitog uses a virtual trawl, replacing a conventional trawl with laser beams. A trawl is a net that drags behind a boat on the seafloor to catch fish. The prawns see the lights and think of it as a barrier, thus the lights act as a net. The laser beams are calibrated to the prawns’ visual capabilities, allowing for only prawn in their catches. This aids with overfishing as it alleviates bycatch. A computer rendered image of the virtual trawl is shown below. There is also a smaller footprint on the surrounding ocean habitats.

A computer generated image of the laser created trawl from Optitog. The lights make the prawn think they are caught in a net.

Not only is this virtual trawl safe for preventing bycatch, but it is also environmentally friendly. Since the ship does not have to drag a heavy, physical trawl through the ocean floor, about 10 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions is saved per kilogram of catch. This is because the ship does not have to pull as hard.

Luring Fish with Lasers

Similar to Optitog with prawns, research has gone into attracting specific fish species with artificial lights. In a paper titled, “Behavioural effects of artificial light on fish species of commercial interest”, Italian scientists studied the effect of lights with different wavelengths on four common species of European fish: European seabass, the common grey mullet, and the gilthead seabream. Fish are attracted to light, so fishermen have been using light to attract fish for years. There is a similar discussion in a previous article on insects’ attraction to light, found here.

The fish were placed in a tank filled with saltwater. The water was maintained at uniform temperature and salinity. A 1000 watt halogen lamp was placed 1 meter away from one side of the tank. Eight different light intensities were tested, along with six colors. The colors were changed by placing different LEE Filters monochrome gelatin sheets in front of the lamp. Violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red were all tested at the same light intensity. The varying light intensities and varying colors were tested separately. The tank was labeled, length wise, into five sections to quantify where the fish were swimming to.

Two of the fish species tended to group together more when the light intensity was decreased, while for the other species they grouped together when the light intensity increased. In relation to colors, the European sea bass tended to aggregate more when shown violet, blue and green. The grey mullet had similar results, as the fish would group together when the light changed from red to violet. On the other hand, the gilthead seabream was not affected by the lights as much. The change in light wavelengths slightly repelled the fish.

This study shows that not only are fish mostly affected by light, but also different species are affected differently. In the future, fishermen may be able to use light tuned to a specific wavelength and intensity to only attract a specific fish species, decreasing bycatch.

Tracking Boats Around the World

Because of overfishing, boats have to travel further and further out to sea to find large amounts of fish. Since these boats are often far out to sea with no supervision, it leads to overfishing rules being broken. These include laws that dictate how many fish can be caught, and what size fish can be kept. Project Eyes on the Sea, a joint project between Pew Charitable Trusts and Satellite Applications Catapult, aims to use satellite imaging and database information to identify groups that are overfishing.

Satellite imagery is one of the ways to track boats in far out waters. Some satellites have synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensors. These satellites orbit daily and take images which can provide information on where boats are located. SAR works by sending out radio waves to an area and capturing the returned echo. A single beam forming antenna receives these echoes which can be at various wavelengths from several meters to just millimeters. Other tactics used to create a comprehensive ship locator include vessel database and tracking. Vessel tracking uses Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, which send out information such as location to ships nearby and low-orbiting commercial satellites. Combining all of this data creates an image like the one below. To find if a vessel is overfishing, analysts look at locations of vessels, their proximity to other vessels, and look into a vessel’s history of overfishing.

A representation of what Project Eyes on the Sea want to create – A map of where every boat is.

A Hope for Overfishing

Fishing has come a long way in the millennia that it has been around for. Extensive machines and technologies are commonplace to catch the largest amount of fish as efficiently as possible. The three different ideas discussed in this article are just the beginning of how the future of fishing may look. With enough research and outreach, photonics may replace bait and nets, reducing bycatch and the risk of overfishing.